The Ruins We Already Have

2025, digital animation, live code interface, digital prints, perfume

Collaboration with Hans Tursack

with sound composition by Nick Kopp

Exhibited at Realms Unreal, The Capital Region Arts Center, Troy, NY

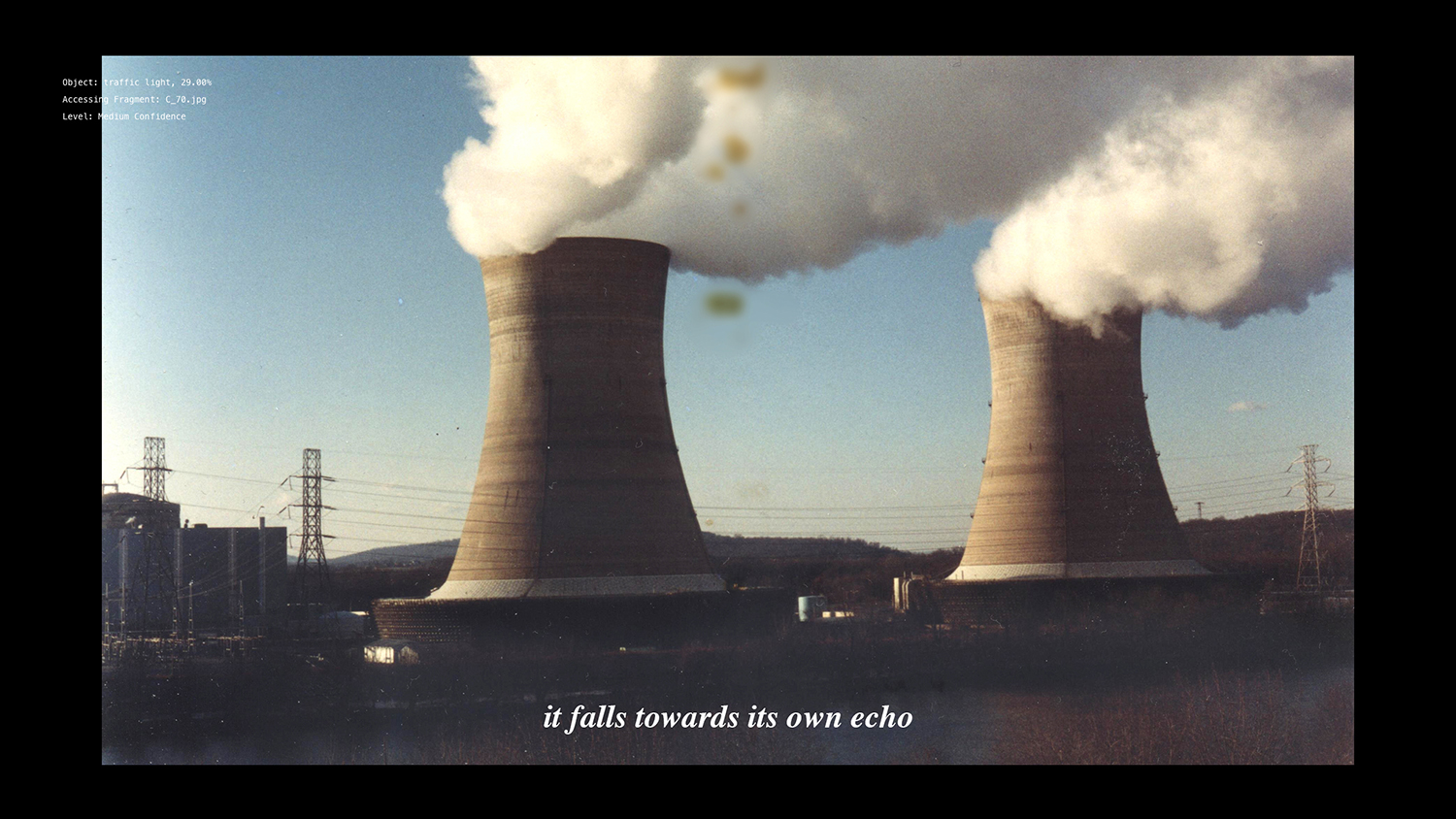

AI is often imagined as an immaterial entity, and both the speed of language models like ChatGPT and usage of terms like “the cloud” provide a veneer of weightlessness. But the cloud is not ethereal; AI has an insatiable demand for energy, increasing our collective ecological risk in a time of desperate need to reduce fossil fuel usage. Microsoft seeks to repurpose the latent energy of nuclear ruins for contemporary digital processes, and in researching its plans, I discovered the ororaborus hiding in plain sight: AI could, in the case of Microsoft’s project, be credited for its own reanimation; the company had an AI sort through enormously complex nuclear regulatory paperwork, training it to generate the documents needed for a lengthy licensing process to re-open Three Mile Island. Microsoft’s AI system was responsible for securing its own power source—one that could not have likely been done by human lawyers alone.

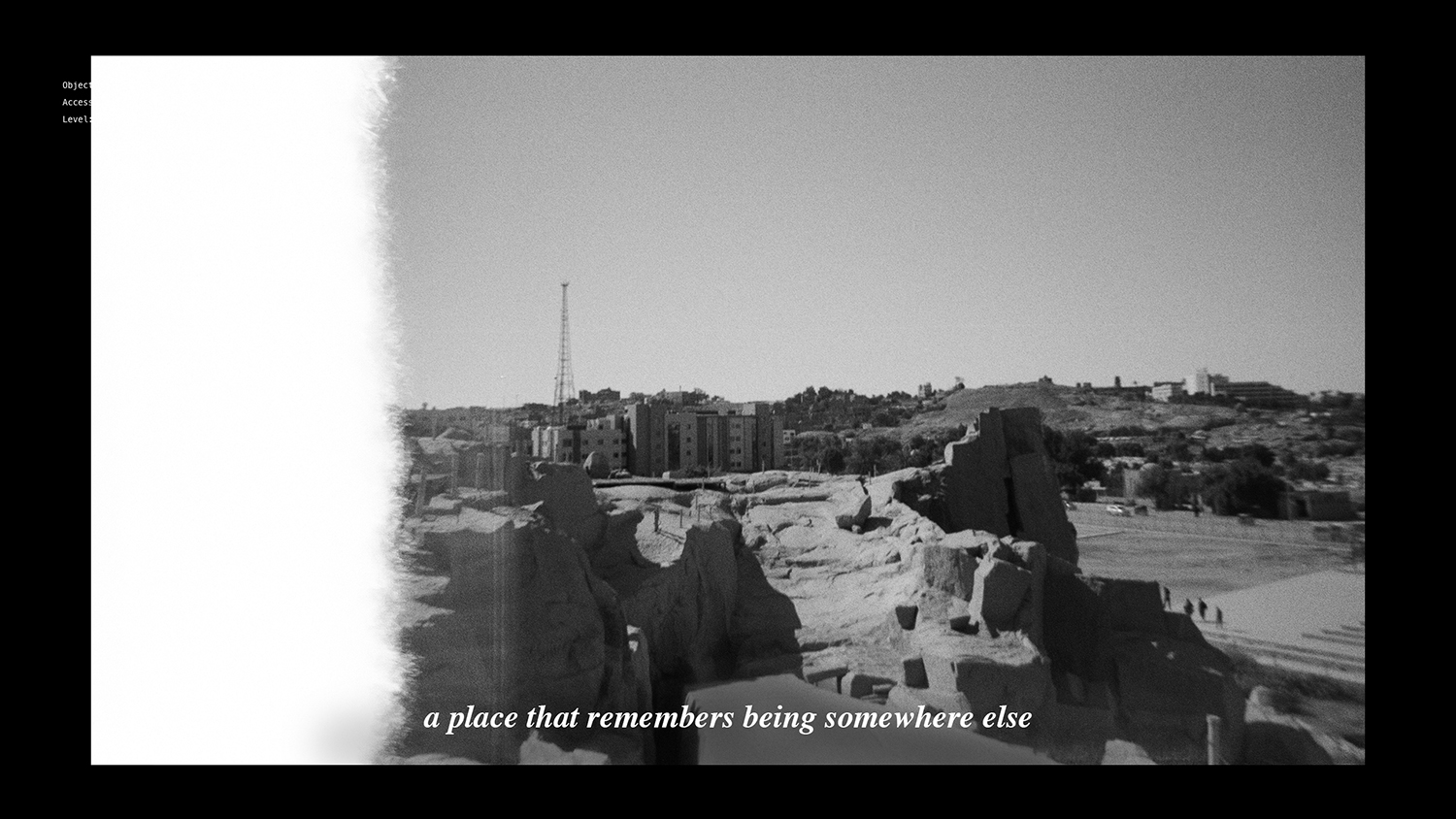

An animation by Tursack on the first screen invited viewers to experience the scale and physics of infrastructure—fragments in motion. In a world increasingly escaping into the imagined futures of science fiction and dystopia, this piece focuses on the ruins that are already here—these fragments of infrastructure and material debris that shape our present. These remnants of abandoned industrial sites, towers, and quarries resist deletion or erasure, demanding attention as sites of both material weight and poetic possibility. Through these digital physics, a process of material empathy is engaged, where our seeing body reacts to the sensation of falling objects. We then used a neural-network-trained program called YOLO (“You Only Look Once”) to analyze Tursack’s animation of fragmented landscapes to recognize objects, producing information in the archetypes of AI logic: pattern recognition and probability of “what this is” or “what comes next.”

This information is representative of how the AI “sees” visuals and form. Instead of using this data literally to tell us about the animation, we instead turned it towards poetics, using it as a selector for a library of photography, archival images and text, which are generated in real time in the exhibition. The text was coded by its level of ambiguity, which corresponded to how confident YOLO was about the objects it was “seeing.” An algorithm running in the exhibition then paired this text with images reflecting my interest in postindustrial detritus and material of Anthropocene landscapes, as well as found imagery which are literally tethered to the material infrastructure that powers it—Three Mile Island.

A hanging olfactory sculpture contains a kind of “late industrial perfume” I designed to combine scents associated with infrastructural ruins (wet concrete, rusty metal), the scent of radiation interacting with the air (reportedly a faint ozone-like smell), and other smells from factories or industrial sites (acrid smoke, burnt plastic). The latter were informed by interviews with my parents, who met in a steel mill in Pennsylvania.

Hans Tursack is a designer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He received a BFA in studio art from the Cooper Union School of Art, and an M.Arch from the Princeton University School of Architecture where he was the recipient of the Underwood Thesis Prize. He has worked in the offices of LEVENBETTS Architects, SAA/Stan Allen Architecture, and Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects. His writing and scholarly work have appeared in Perspecta Journal, Pidgin Magazine, Plat, Crop Journal, Thresholds Journal, Log Journal and Acadia. He was the 2018-2021 Pietro Belluschi Fellow at the MIT School of Architecture + Planning and a Visiting Assistant Professor at the Sam Fox School, Washington University in St. Louis (2022-2023). Hans is currently a PhD student in Electronic Arts at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Department of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences.