Transcorporeal

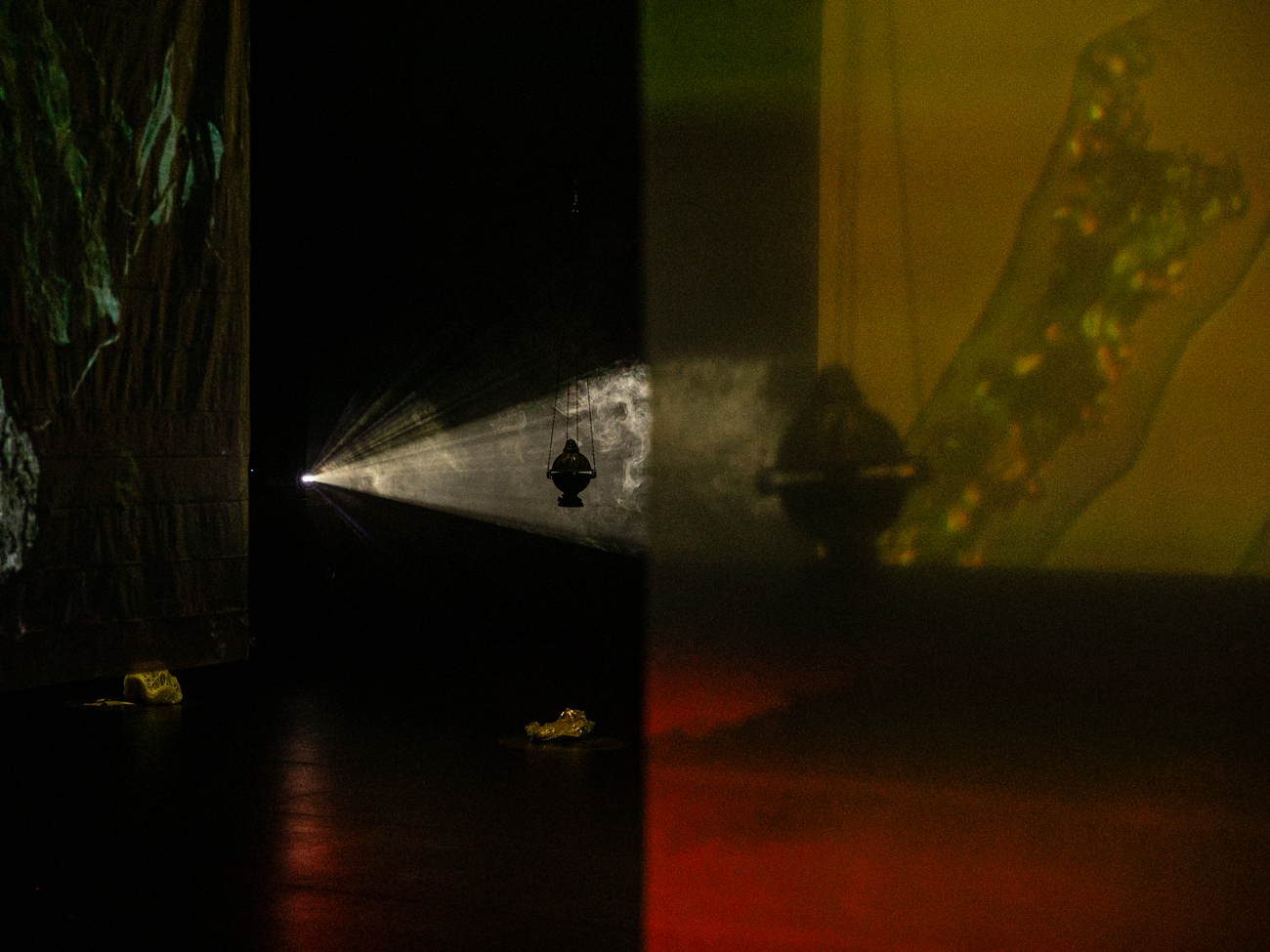

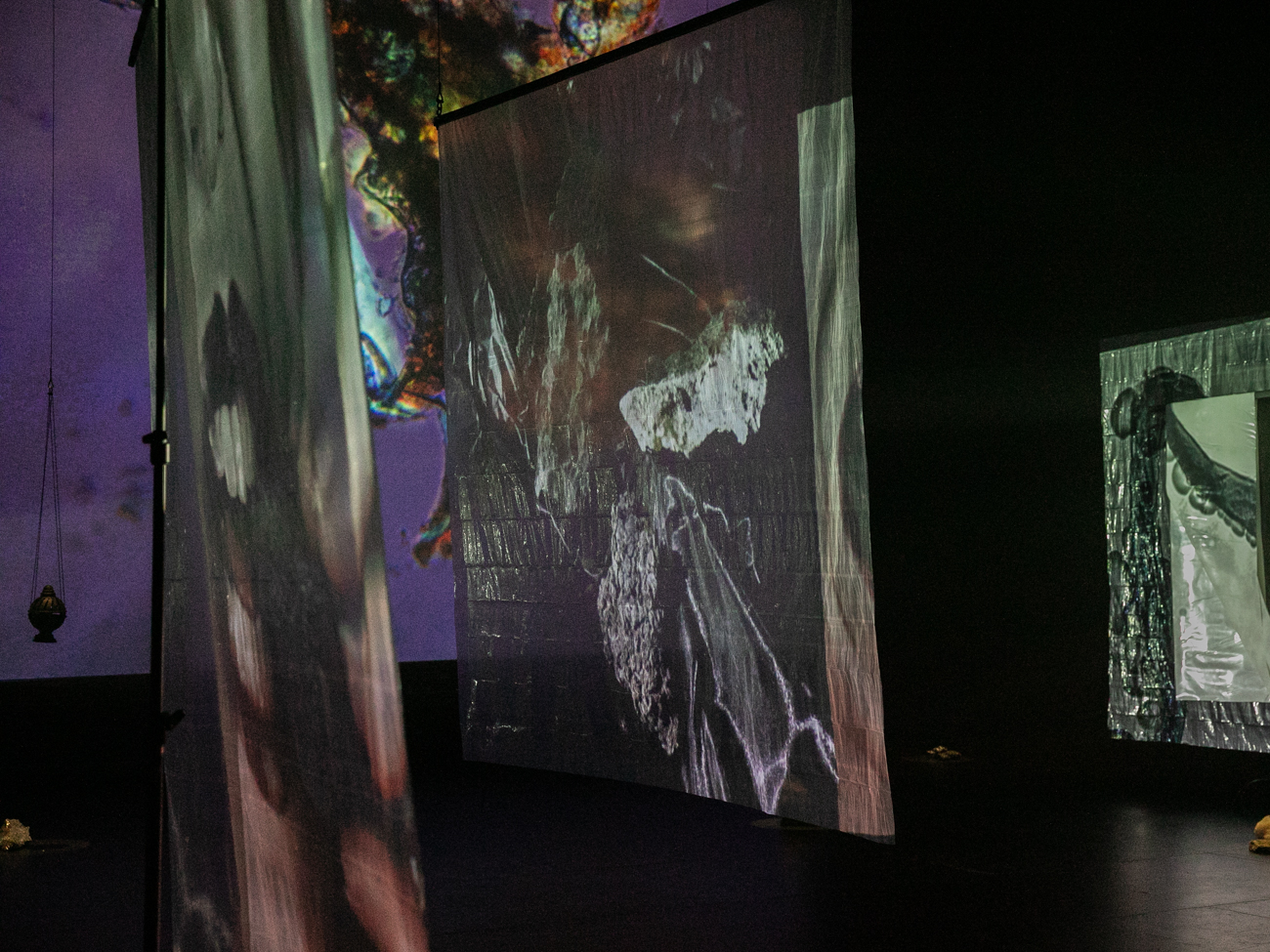

2024, installation with video, ambisonic sound, scent, 3D-printed incense burners, poly-plastic sheeting, anthropogenic geology

Completed during a residency at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, Troy, NY

The ambiguities of the toxic sublime are bridged across sensory registers as purity politcs become visible through acts of consumption.

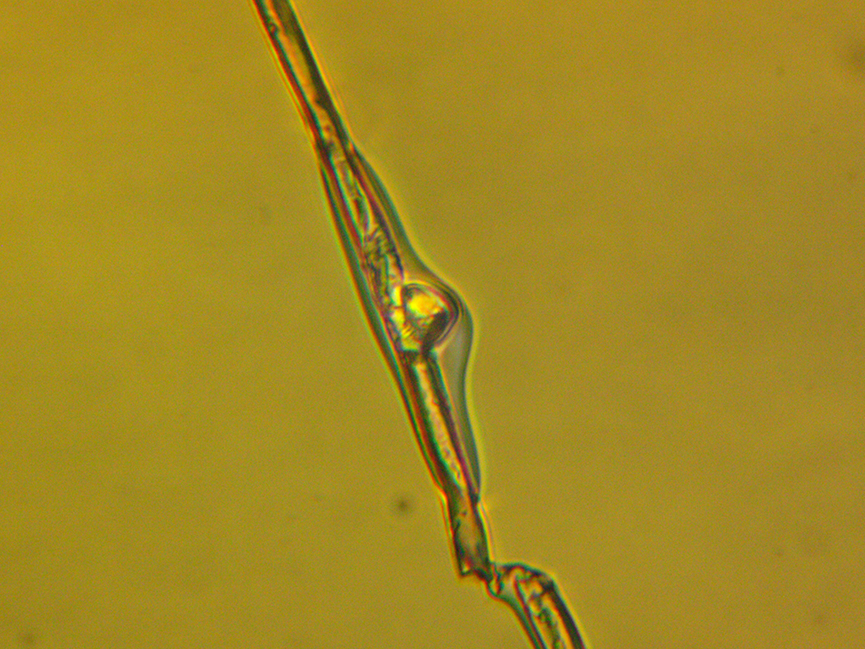

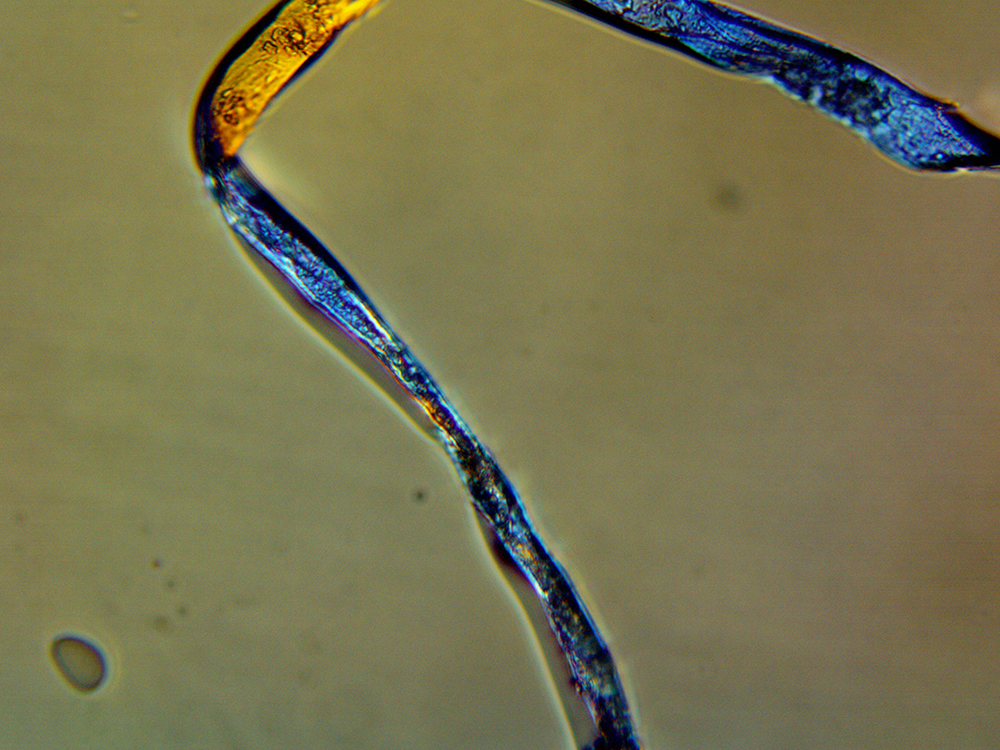

A series of custom screens made from plastic poly-sheeting turned EMPAC’s Studio 1 into a space forreflection of (and from inside) various scalar and material agencies of the Anthropocene. Live and captured microscope projections showed the artists’ search for microplastics in local tap water, while other videos showed the consumption of edible clay rocks (geophagy) and edible plastics. Hanging incense burners filled the atmosphere with petro-aesthetic scents designed to replicate wet asphalt, acrid smoke, burnt plastics, and other invisible risks of late industrialisms.

This work is meant to provide viewers with a space for sensing where boundaries and distinctions breakdown—where the limits of one body become fuzzy with another, when detritus finally becomes landscape again, when the distinction between “natural” and human-made is no longer functional.

Are the microplastics in my blood considered waste? Or are they now human?

Microplastics have been found in placenta and infant feces, meaning that babies are born with plastic in their bodies; it is a new kind of original sin. In a wellness-plagued culture that too-often seeks purity, how do we learn to live as exposed and toxic bodies? The question now might be “How to be Not Well,” as writer Sophie Strand has suggested, and in fact, Strand offers the affirmation: “I Will Not be Purified.”2 Similarly, M. Murphy asks us to take seriously the acceptance of what they call alterlife—life already, irrevocably altered by ongoing ecological violence.3 But life altered is also a capacity for becoming something else. It is life no longer “waiting for the apocalypse” to arrive.3

It is building worlds from within the disaster.

Microscopy footage captured as part of a citizen science project run by Dr. Sarah Cadieux, with support from NATURE Lab, Kathy High, and Ellie Irons.

The exhibit also featured an olfactory entrance chamber designed for deprivation of the senses which most often take primacy in scientific knowledge production—sight, sound, and even touch.

Before entering the main installation space, the audience was asked to stop in this darkness to smell a single hanging sachet containg the scent of a complex perfume designed to remind visitors of asphalt tar. The smell alluded to toxicity without actually being toxic, bringing forth the agency of nonhuman materials and invisible chemical atmospheres. Microphones captured their reactions to the perfume, which were incorporated into the main installation soundscape on a 3 minute delay.

The subjectivity and corporeality of olfaction does not preclude it from being a valid form of knowledge of our environment, and in fact, may be a benefit to understanding the lived realities of ecological collapse. In the 19th and 20th centuries, smell was a legitimate way to understand environmental changes, as toxic industrial pollution was frequently reported via its noxious odor. Smell provides evidence of manufactured risks that may be unperceived by the naked eye, pervasive in late industrialisms.

A ‘materials archive’ of Anthropogenic geology was installed across the floor of Studio 1 as terrain; this unhierarchical archive contained objects typically left out of natural history museums, which I suggest are falsely separated from “natural” geology.

The collection of hybrid rocks are ones formed in the aftermath of industrial processes, including from incinerators, glass-making factories, military operations, plastic extruders, urban paving, steel mills, and garbage incinerators. Some are shrink-wrapped in plastic—a gesture at geologic pressure through time, pressing these objects into a record of after nature.

1. Stacy Alaimo, and Susan Hekman, eds. Material Feminisms (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008).

2. Sophie Strand, “I Will Not Be Purified,” ArtPapers 45.01, Fall 2021.

3. Michelle Murphy, “What Can’t a Body Do?,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 3,no. 1 (2017).