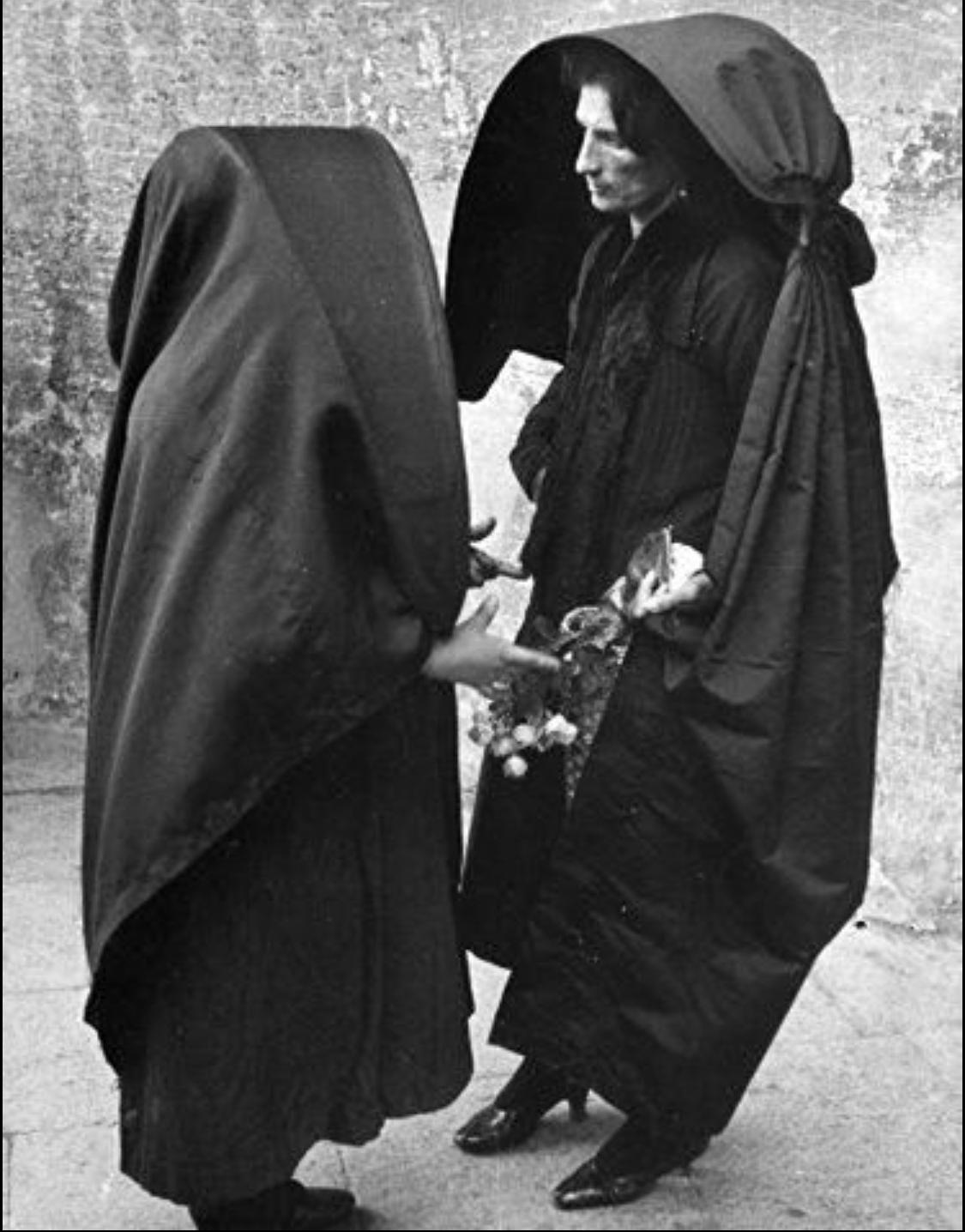

Agricultural Sorrower, 2022

This work was performed as part of a collaborative project entitled Future Folk by Zé (Jefferson) Kielwagen.

This funerary costume is made from agricltuural materials that serve as supressants of life, or as means of containment: bird netting, landscaping fabric for weeds, and chicken wire. It also incorporates black plastic netting as a veil, which is a material used on farms that are experiencing extreme temperatures and desertification / high average temperatures. These materials simultaneously speak to the precartiy of global agriculture in an Anthropocene world, as well as the harsh realities of containment enacted through frameworks deliniating binaries between nature/culture. Agriculture has been posited as a possible start date for the Anthropocene—a moment when humans began geo-engineering the earth at scale and creating lasting human “marks” or changes to earth systems functioning. A

More broadly, agriculture represents a primary example of post-natural landscapes, as domesticated plants and animals challenge the kinds of ontological hygiene which keep humans separate from so-called nature. Industrial agriculture might be one of the best examples of plastified nature—“plastic” in that it replicates the mentality of plasticity and attempts to create synthetic universality (Heather Davis, Plastic Matters). Indeed, hegemony in the form of monocropping is one of agriculture’s greatest accomplishments; It rests on an imaginary where humans have control over nature through a globalized and industrailized food system.

The black materials of the Sorrower speak to the many attemtps, especially in the history of the West, to execute control over nature. Their color is not inconsequential; as black absorbs all color of the light spectrum, the materials, too, absorb the interactions and inevitabillities of a greif-stricken post-natural world.

Performers in Future Folk were all costumed in anthropogenic materials, and formed an excrutiatingly slow procession in downtown Troy, New York (Oct 2022).

This funerary costume is made from agricltuural materials that serve as supressants of life, or as means of containment: bird netting, landscaping fabric for weeds, and chicken wire. It also incorporates black plastic netting as a veil, which is a material used on farms that are experiencing extreme temperatures and desertification / high average temperatures. These materials simultaneously speak to the precartiy of global agriculture in an Anthropocene world, as well as the harsh realities of containment enacted through frameworks deliniating binaries between nature/culture. Agriculture has been posited as a possible start date for the Anthropocene—a moment when humans began geo-engineering the earth at scale and creating lasting human “marks” or changes to earth systems functioning. A

More broadly, agriculture represents a primary example of post-natural landscapes, as domesticated plants and animals challenge the kinds of ontological hygiene which keep humans separate from so-called nature. Industrial agriculture might be one of the best examples of plastified nature—“plastic” in that it replicates the mentality of plasticity and attempts to create synthetic universality (Heather Davis, Plastic Matters). Indeed, hegemony in the form of monocropping is one of agriculture’s greatest accomplishments; It rests on an imaginary where humans have control over nature through a globalized and industrailized food system.

The black materials of the Sorrower speak to the many attemtps, especially in the history of the West, to execute control over nature. Their color is not inconsequential; as black absorbs all color of the light spectrum, the materials, too, absorb the interactions and inevitabillities of a greif-stricken post-natural world.

Performers in Future Folk were all costumed in anthropogenic materials, and formed an excrutiatingly slow procession in downtown Troy, New York (Oct 2022).

From Kielwagen:

“The project proposes new forms of folklore, new cultural forms fit for the apocalypse... It responds to Mark Fisher’s concerns, by exposing the Real concealed by capitalist realism. It responds to Claire Bishop’s critique of relational art by producing uneasy relationships. It rises to a challenge posed by Slavoj Zizek in Examined Life: to re-create an aesthetic dimension, poetry and spirituality, in trash. It follows David le Breton in employing slowness and silence as strategies of resistance.”

![]()

![]()

“The project proposes new forms of folklore, new cultural forms fit for the apocalypse... It responds to Mark Fisher’s concerns, by exposing the Real concealed by capitalist realism. It responds to Claire Bishop’s critique of relational art by producing uneasy relationships. It rises to a challenge posed by Slavoj Zizek in Examined Life: to re-create an aesthetic dimension, poetry and spirituality, in trash. It follows David le Breton in employing slowness and silence as strategies of resistance.”

Documentation by Ava Goucher and Fatima Kamara