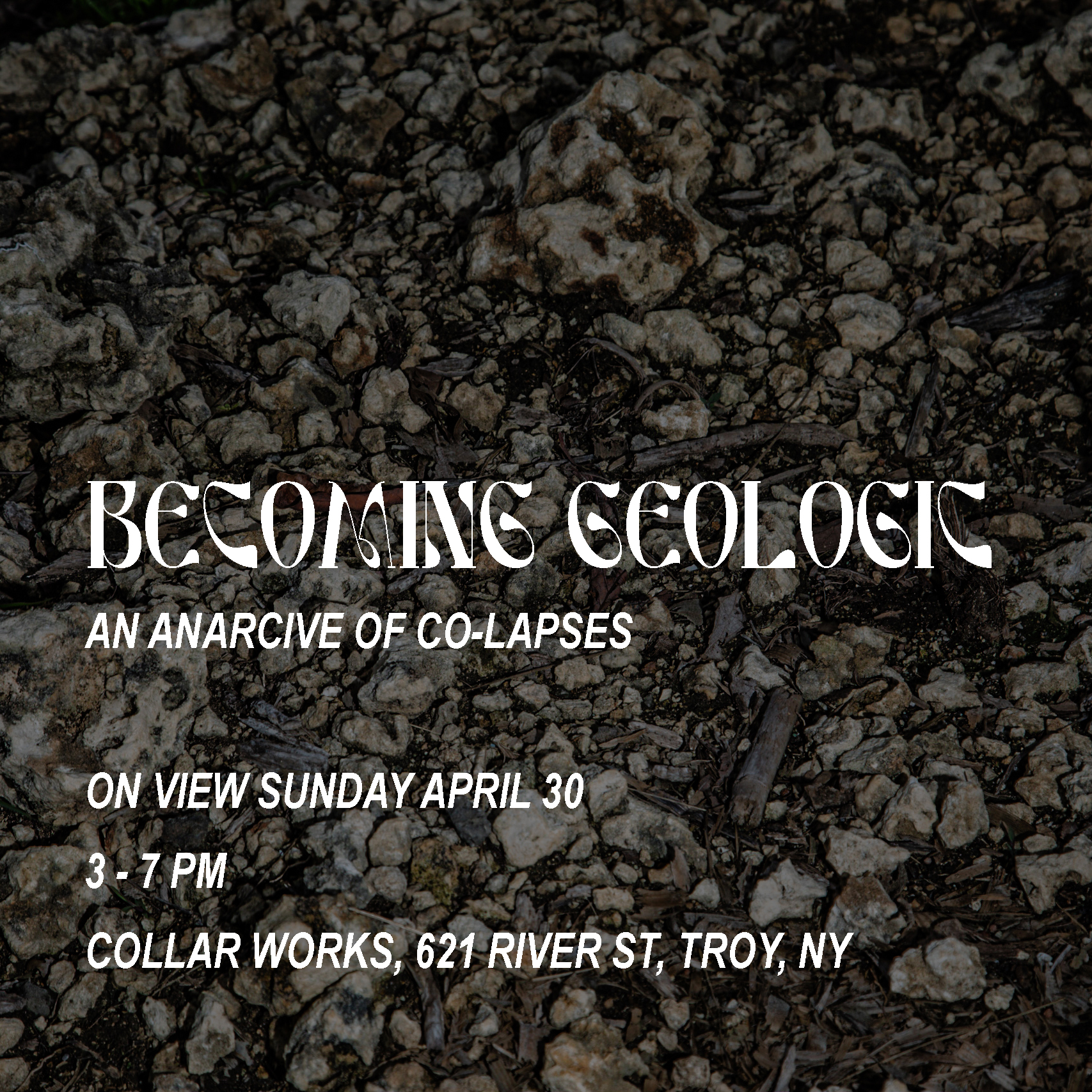

Becoming Geologic

May, 2023, Collar Works, Troy, NY

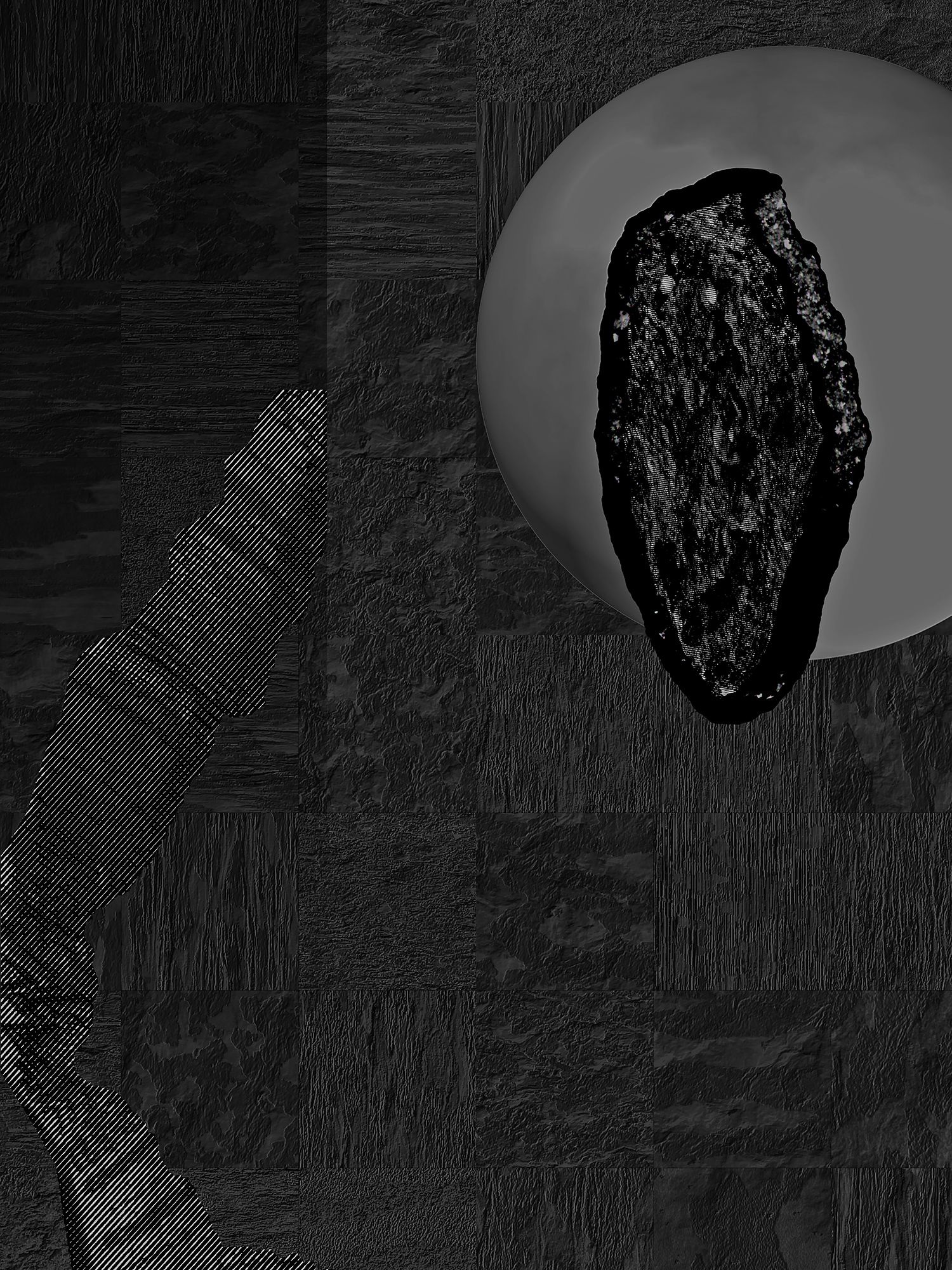

Mixed-media installation with gravel; metal; bread; edible clay; scents; various human-made rocks and aggregates; cinderblock with dough; clay and charcoal sorhgum rolls; audio recordings; digital print (24x32); vinyl mesh print.

“The body is a good place for collapsing human and geologic timescales.” —Iemanjá Brown

This installation was comprised of three archival “rooms” containing various iterations of a speculative natural history Anthropocene archive, and anthropogenic future strata, involving human bodies in geologic processes.

The first room functioned as an exhibit of artifacts from present-future anthropogenic metabolism—what might be considered future strata, from the perspective of a distant geologist or archeologist hundreds or thousands of years form now. These include: asphalt from the edges of parking lots and roadways; improperly mixed concrete or other aggregates left as waste; steel mill slag; byproduct glass “rocks” from industrial ruins; melded iron-sediment-waste “rocks” from an uncapped landfill; remnants from infastructure such as concrete swimming pools or demolished homes. Prompts in the room invited visitors to describe various “rocks” to this future stratigrapher, asking for an ongoing construction of meaning and matter.

Metabolism can, at the same time, be individual or collective and both biological and social. Metabolic processes swell beyond the scale of the individual body, as humans collectively accumulate their activity to extract matter and energy from nature; these extractions flow through society and result in a host of wastes and biophysical residues excreted back into the environment. It proves to be a looping and multi-directional process, as toxins we put into the earth, like heavy metals, end up back in our bodies as lead poisoning.

Social Metabolism (S.M.) describes the material exchanges human societies have with the environment to maintain order and life functioning. Since the late 1990s, the concept of anthropogenic metabolic flow gained tenacity for accounting for the activity and environmental impacts of industrial societies. It is a way to conceive of what the earth, and various landscapes, have to metabolize, or digest, of human inputs.

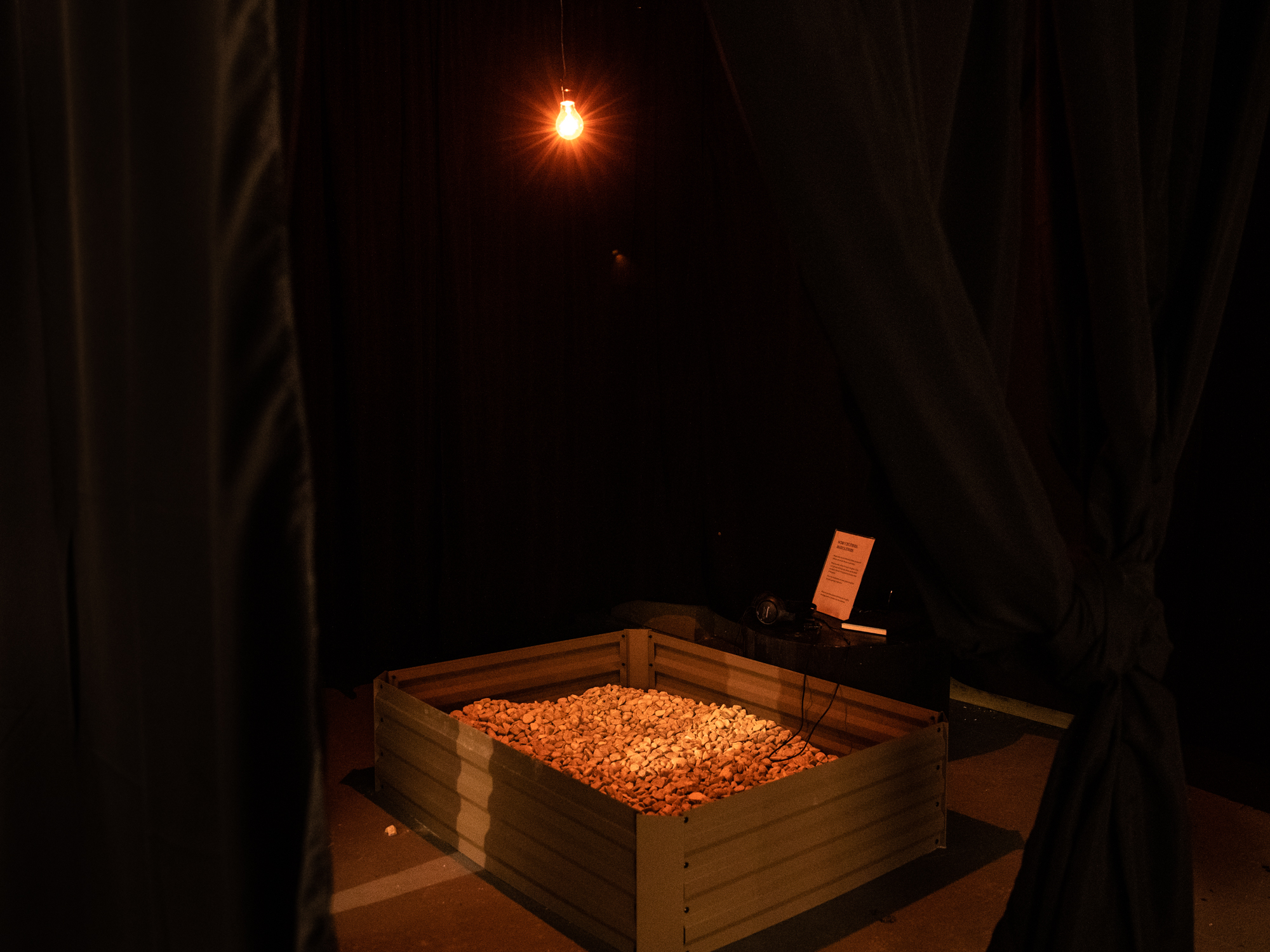

A geologic meditation room allows ones’ body to reflect on its material porousness with earth and its likeness to stone. Visitors are asked to sit or lay in a bed of gravel and put on headphones to be guided through an “aggregate” meditation. This engagement permits an experience of other shapes of time—of the time of rocks, natural or otherwise. Perhaps an experience of becoming a rock changes environments as we exist within them because it changes our perception of the materials in them.

A room of edible and olfactory artifacts interrupt the alienation of planetary-wide discourse and invite subjective, corporeal experiences of the Anthropocene. By eating clay and charcoal, or by inhaling tar perfume, we might process landscapes with our body as they have been digesting our own inputs. We sense the vulnerability of having to digest back the pollutants and toxic materials we have put into the earth. Our chemcial senses (taste and smell) are visceral senses which bypass cognition, animating memory and emotion more directly than sight or sound. These senses can be our most intimate contacts with landscapes that otherwise function at scales of time and space we cannot easily access. Smell, taste, and digestion are forms of sensing that act as more intimate alternatives to simply being “consumers,” and thus, to extraction and degradation.

Becoming Geologic Exhibition Text

APRIL 28, 2023

Becoming Geologic rejects the species-wide anthro-

Becoming Geologic does not adhere to a universal -cene

Sensing the Anthropocene involves multiple material tempos, lapses of memory, and futures made in a nonsynchronous Now. It is about sensing time lags, it is about falling together. The phantom of flowing, uni-directional time haunts us all, implying a universal history we never had.[1]

Becoming Geologic is becoming toxic, becoming aggregate, becoming sticky and porous. This is a mutual process of digestion and metabolism between our bodies and rock, soil, and earth. Bodies which can sense the intensities of the actual-now, the falling apart, the emergent and the what-might-be. The real and the potential shimmer in and out of each other in the momentary intensities of the present. Fact and felt are indistinguishable as a body moves through space. It is only when we look to the past that our affective bodies evaporate, and rational accounts of geologic time favor universalized facts over precious felt experience itself.

In a 1977 essay on how capitalist modernization creates a time lag in social worlds, Ernst Bloch severs the present moment: “Not all people exist in the same Now.”[2] His essay hinges on the experience of the rural proletariat in Germany, whose adherence to certain material practices of the past caused them to live in the present nonsynchronistically. (This, he argues, is why they fell for Hitler’s propaganda and explains the rise of Nazism.) The rural class’s ownership of the means of production (as farmers), their contact with the soil, and their engagement with material practices sewed them into an earlier timeline, different from that of urban citizens.

The idea that not everyone exists in the present moment the same way—that we are contemporaneously not all contemporary—can be extended into the concept of the Anthropocene. Fossilized bodies from the past, in the form of fossil fuels, “emerge in the Now and send a bit of prehistoric life into it.”[3] Material bodies, human and non, will continue to emerge onto future timelines, as ruptures and meshy selves of more than one contemporariness. Some objects, like plastic waste or concrete, are the physical alignment with past tempos—the time demands of capitalism and consumerism—despite a far future where those rhythms may have long dropped out. The materials’ slow degradation means they experience the same kind of time lag, stitching “our” past onto a distant future.

Despite the presumptiveness of a contemporaneous Now, shared unilaterally, this is a construct of a Western and deeply modern origin.[4] It is as pernicious as it is constructed, so deeply built into our perception is one universal timeline, that considerations of other time and others’ time—bacterial time, decomposition time, digestion time—are continually still mapped along a unidirectional arch. (Even seemingly more-than-human spans of scientific timeslines, like geologic deep time, are still a product of a specific linear time.)

But humans’ own accounts of time in pre-Modern societies were often cyclical, or dismissed the supremacy of chronological time.[5] The image of a universal flow which emerges more acutely in Modernity, according to Siegfried Kracauer, “only veils the divergent times in which substantial sequences of events materialize.”[7] And now, in the age of the Anthropocene, the notion of many times, with many shapes, stands to overshadow the perceived universal flow.[6] Uncontained swells of material waste, toxicity, and biological extinction pushes against the edges of comforting, flowing time. The many-shaped times of fossil fuels, bacterial mutations, pollutant flows, and human infrastructure contain sequences of material transformations, simultaneously overlapping, looping, lurching and meshing within the perceived Now.

Much of the premise of my work hinges on the concept of an archive[8]—the lineage of which is deeply indebted to linear time. Archives are typically a locus of authority and become repositories of accumulated knowledge,[9]constructed in alignment with Western notions of time. The presence of an archive implies a past we can be reassured of, reified by artifacts rendered as objective through processes of preservation. Natural history collections in particular rest centrally on the accumulation of objects[10] and prioritize static, inert dead matter[11]—these materials’ provide evidence of a past, reassuring us of unidirectional progress. Sealed behind glass, rendered inert via taxidermy, or replicated in non-decaying materials, artifacts in archives suggest the past is discrete, and that everything that science can account for, ultimately, adheres to humans’ felt sense of time. They answer question of where we are from, and suggest where we are headed,[12] obscuring any question of the temporal direction assumed.

Geologic archives had specific industrial and modernist aims, growing from of a desire to create reliable knowledge concerning the distribution of ore for extractive mining practices.[13] Major developments in natural history archives “drew on centuries of experience derived from intensive mining practices,”[14] deeply implicating them in extractive capitalism and colonialism—two major drivers of the Anthropocene. The collection of rocks and minerals now housed in museum archives acutely reflect the dualist space/time of Modernity, falsely bifurcating humans from nature, and suggesting an impossible God’s eye view of planetary change which forecloses loops and meshy overlaps in co-constructed time(s).

In our current classifications of minerals, strata, and rocks, we are called to question geology itself, and following Kathryn Yussof’s thesis in A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, we may better reference White Geology specifically. Yussoff writes that by conceiving of the past within “present colonial mining empires of white settler nations,” we are able to name “White Geology as a historical regime of material power, not a genetic imaginary”[15]Geology is a construct which rests on material practices of extraction, and furthermore, on the differentiation between the human and the inhuman (its subcategory) as a settler-colonial discourse categorizing matter.[16]Not to say that a constructivist orientation towards White Geology automatically admits aggregates or synthetic materials to natural history archives, but it importantly points to the violence of taxonomizing—differentiating the human from nature, natural from man-made, edible from waste—which serves the extractive practices driving the Anthropocene. The history of rock and mineral classification has been, in fact, fueled by centuries of extractive mining practices.[17]

While the first part of the new epoch (anthros) has been roundly debated for its implication of “all humans” in a phenomenon better attributed to the systems of capitalism, plantation agriculture, or colonialism, the latter part of the word (cene) has remained curiously unchallenged.[18] But geologic time rests on the assumption of universal chronologic time, which reinforces human exceptionalism.[19] As scholar Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent articulates, epochal notions of deep geologic time, progressing linear from one stage to the next, is “but one way of experiencing time and the current crises invite us to assume a variety of times, to adopt of polychromic view.”[20] The alien, unruly, and manifest horrors of ecological crisis call into question our adherence to one time, to a simultaneous Now. They suggest abandoning the implied human<>nature divide lurking in the -cene. Perhaps they also suggest we can still co-create pasts as well as futures in a polychromic Now, filled with nonsynchronous beings.

Archives were never, actually, definitively about the past.[21] The inscription of the past is inherently also a promise of a future, dependent on what is to come, and as such, archives are constantly opening towards the future.[22] The anarchive more explicitly concerns itself with process and time-based sensations over finite objects; it rejects the Now that prevents past and future from being altered. It is fundamentally concerned with the process of becoming-other. The archival processes and works in Becoming Geological reflect change that is still ongoing, unsettled, or ephemeral, emphasizing the Anthropocene’s unique temporal dimensions and multi-temporalities. The main access point for the polychromic and nonsynchronous is the sensing body, which can be both grounded in the real, someone’s Now, and non-metaphorically materially creating past and futures.[23]

Bodies are a resonant medium for temporality—for the intensities of the actual-now, the falling apart, the emergent and the what-might-be. The real and the potential shimmer in and out of each other in the momentary intensities of the present. Fact and felt are indistinguishable as a body moves through space. It is only when we look to the past that these affective bodies evaporate, and rational accounts of history or geologic time favor universalized, objective facts over precious felt experience itself. We erase the sensing and affective qualities of experience, despite their construction, not just of meaning,[24]but of the individual body itself[25]and of world as it is.[26]The sensing body contributes to what constitutes the real, not just in beingbut also in becoming, and how we open towards the future. Our bodies can hold space for a comingling of time, of other bodies’ time, of breakdowns in dualisms and ontologies.

In Becoming Geologic, these themes come together in the form of digestion and metabolism in the Anthropocene. Processes of digestion and metabolism reflect the time of microbial worlds, of nonlinear flows, and of things-more-than-themselves. They are sensory and embodied, existing as fleshy time-shapes stuck awkwardly and voluminously onto rigid and lonely swaths of deep time. These processes become the transformational frameworks to permit ontological breakdowns between human-made materials and nature, and to allow corporeally involvement in accounting for timewith materials themselves. The AnArchive presented in Becoming Geologic has three stages: (1) a geologic meditation that allows ones’ body to reflect on its material porousness with earth and its likeness to stone. It permits an experience of other shapes of time. A body resonates with pasts, with material processes unfolding, and with swells and pulls in one direction or another. Our experience with and as rocks changes environments as we exist within them because it changes our perception of them. (2) An exhibit of present-future anthropogenic metabolism[27]artifacts asks for an ongoing construction of meaning and matter. (3) A room of edible and olfactory artifacts suggests that by eating clay, charcoal, and earth we might process landscapes with our body as they have been digesting our own inputs. We sense the vulnerability of having to digest back the pollutants and toxic materials we have put into the earth.[28] Taste and digestion can become a form of sensing that act as an alternative to simply “consuming,” and thus, to extraction and degradation. In the words of scholar Iemanjá Brown, appetite is an “aesthetic procedure that includes a material desire for intimacy with the more-than-human.“[29] Eating represents a kind of “knowing” that is not simply inherent to a natural body perceiving the world around itself but that arises from interaction with parts of the world in a sensory capacity.[30] It is inherently relational, and involves us in epochs we’d otherwise only perceive from a God’s eye view. Eating clay, tasting ashen charcoal breads, and inhaling dirt in the midst of a climate crisis is a commitment to permitting the state of the earth “directly in our body.”[31] Brown continues:

“The body is a good place for collapsing human and geologic timescales… bodies are able to contain and collapse a thing that language can't... Eating is anticipatory because food helps the body ‘live into an environment in its future.’ If eating becomes anticipation of a future milieu, how does dirt eating represent, and therefore start to posit into existence, some different World to step into; what sorts futures are being invoked when dirt is consciously ingested? Perhaps one … where the human body is seen as a porous conductor of toxicity in the ground.”[32]

Consumption and inhalation are both sensory means of bringing other times into the Now, and permitting contact with an ambiguous sense of contamination at the heart of the Anthropocene. Perfumes of asphalt and dirt encourage the acceptance the a porousness and melancholy of bodies bound up in so many other bodies. Brown and black breads and chunks of edible clay are not artifacts in and of themselves, but are artifacts of the potential for mutual, material transformation.

Becoming Geologic is about a mutually constitutive version of geology—it is about verbs that are camouflaged as nouns. Aggregate, rock, earth. It is about shared fallings-together and co-lapses in time. It is a felt sensethat human-made materials are no longer discrete from geology, as they continue to re-manifest in landscapes, in our bodies, and in the atmosphere, transcending yet collapsing timescales within them.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

Barad, Karen, and Adam Kleinman. “Intra-Actions.” Mousse Magazine 34 (2012): 76–81.

Bensaude-Vincent, Bernadette. “Rethinking Time in Response to the Anthropocene: From Timescales to Timescapes.” The Anthropocene Review9, no. 2 (2021): 206–19.

Bloch, Ernst. “Nonsynchronism and the Obligation to Its Dialectics.” New German Critique 11, no. Spring 1977 (1977): 22–38.

Brown, Iemanjá. “Through the Mouth: An Essay on Appetite and Ecocide,” diss., The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2019.

Brown, Iemanjá. “Dirt Eating in the Disaster.” In Timescales: Thinking Across Ecological Temporalities, edited by Bethany Wiggin, Carolyn Fornoff, and Patricia Eunji Kim, 169–81. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Brunner, Paul, and Helmut Rechberger. “Anthropogenic Metabolism and Environmental Legacies.” Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change 3 (2001): 54–72.

Förster, Desiree. Aesthetic Experience of Metabolic Processes. Lüneburg: meson press, 2021.

Gatens, Moira. Imaginary Bodies: Ethics, Power and Corporeality. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Grosz, Elizabeth. The Incorporeal: Ontology, Ethics, and the Limits of Materialism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017.

Guntau, Martin. “The Natural History of the Earth.” In Cultures of Natural History, edited by N Jardine, J. A. Secord, and E. C. Spary, 211–29. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “Time and History.”History and Theory 6 (1966): 65–78.

Winsor, Mary. “Museums.” In The Cambridge History of Science: Volume 6: The Modern Biological and Earth Sciences, edited by John V. Pickstone, and Peter J. Bowler, 60–75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Wist, Allie E.S. “Anarchives for the Anthropocene.” Technoetic Arts 21, no. 2 (forthcoming): np.

[1] Siegfried Kracauer, “Time and History,” History and Theory 6 (1966).

[2] Ernst Bloch, “Nonsynchronism and the Obligation to Its Dialectics,” New German Critique 11, no. Spring 1977 (1977), 23.

[3] Bloch, “Nonsynchronism and the Obligation to Its Dialectics,” 24.

[4] Kracauer, “Time and History.”

[5] Kracauer, “Time and History.”

[6] Kracauer, “Time and History,” 68.

[7] Kracauer, “Time and History,” 68.

[8] Allie E.S. Wist, “Anarchives for the Anthropocene,” Technoetic Arts 21, no. 2 (forthcoming).,

[9] Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” Diacritics25, no. 2 (1995).

[10] Mary Winsor, “Museums,” in The Cambridge History of Science: Volume 6: The Modern Biological and Earth Sciences, ed. John V. Pickstone, and Peter J. Bowler (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

[11] Stephanie Springgay, Anise Truman, and Sara MacLean, “Socially Engaged Art, Experimental Pedagogies, and Anarchiving as Research-Creation,” Qualitative Inquiry 26, no. 7 (2020).

[12] Kracauer, “Time and History.”,

[13] Martin Guntau, “The Natural History of the Earth,” in Cultures of Natural History, ed. N Jardine, J. A. Secord, and E. C. Spary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996)., 211.

[14] Guntau, “The Natural History of the Earth.”, 214.

[15] Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 15.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Guntau, “The Natural History of the Earth.”

[18] Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent, “Rethinking Time in Response to the Anthropocene: From Timescales to Timescapes,” The Anthropocene Review 9, no. 2 (2021).

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression.”

[22] Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” 24.

[23] Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

[24] Moira Gatens, Imaginary Bodies: Ethics, Power and Corporeality (New York: Routledge, 1996).

[25] Karen Barad, and Adam Kleinman, “Intra-Actions,” Mousse Magazine 34 (2012).

[26] Elizabeth Grosz, The Incorporeal: Ontology, Ethics, and the Limits of Materialism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017).

[27] Paul Brunner, and Helmut Rechberger, “Anthropogenic Metabolism and Environmental Legacies,” Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change3 (2001): 54-72.

[28] Clay-eating has been cited among animals and humans as a means of removing toxins from plants to be consumed, positioning it as an unexpected agent within the purity<>toxicity spectrum.

[29] Iemanjá Brown, “Through the Mouth: An Essay on Appetite and Ecocide,” diss., The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2019), 5.

[30] Allie E.S. Wist, “Sensory Knowledge for Changing Landscapes,” APRIA Journal, 2022, September 8, https://apria.artez.nl/sensory-knowledge-for-changing-landscapes/.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Iemanjá Brown, “Dirt Eating in the Disaster,” in Timescales: Thinking Across Ecological Temporalities, ed. Bethany Wiggin, Carolyn Fornoff, and Patricia Eunji Kim (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020). Citing Hannah Landecker, “Postindustrial Metabolism: Fat Knowledge,” Public Culture 25, no.3 (2013): 509-10.