Transcorporeal, 2024

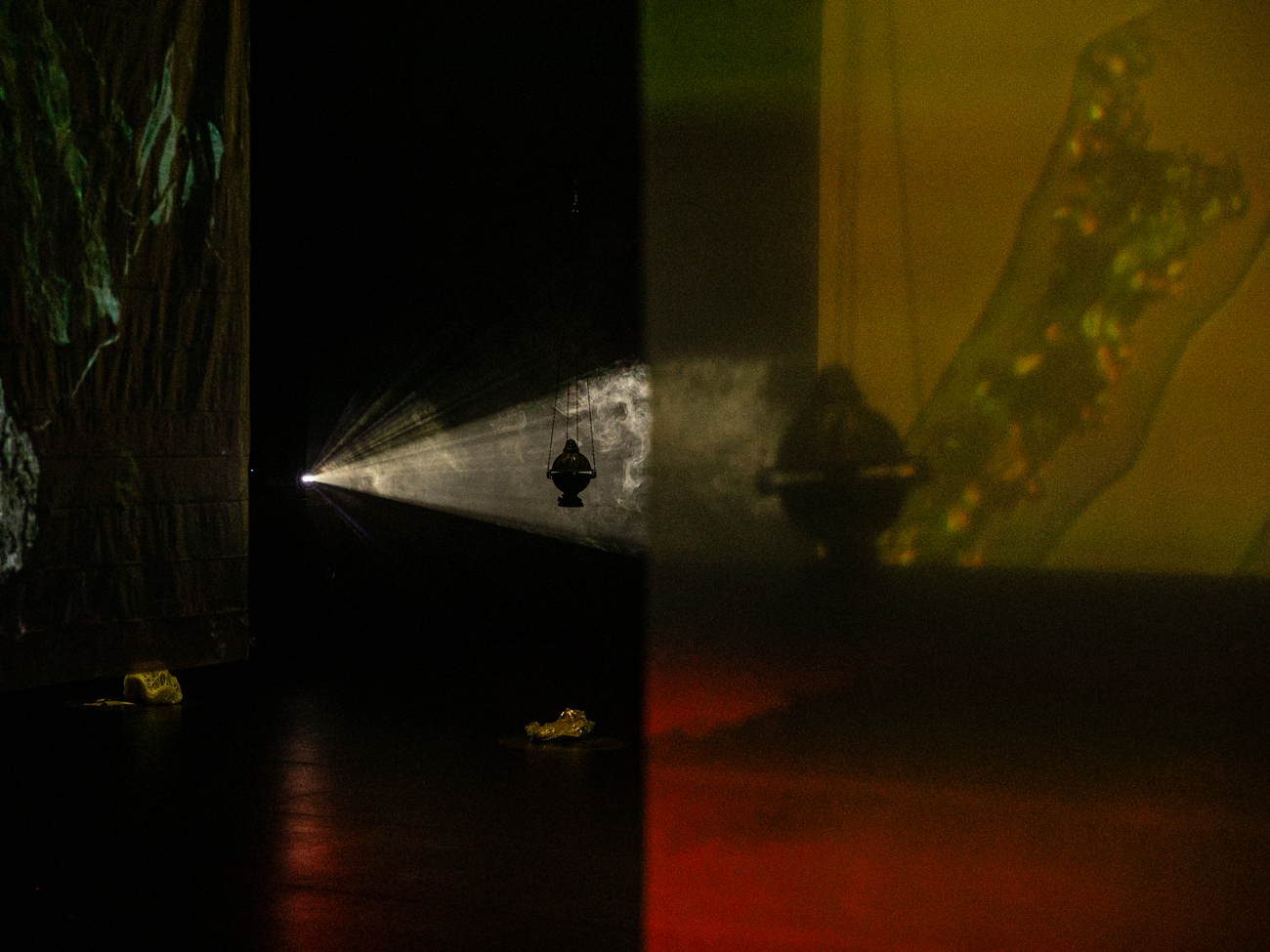

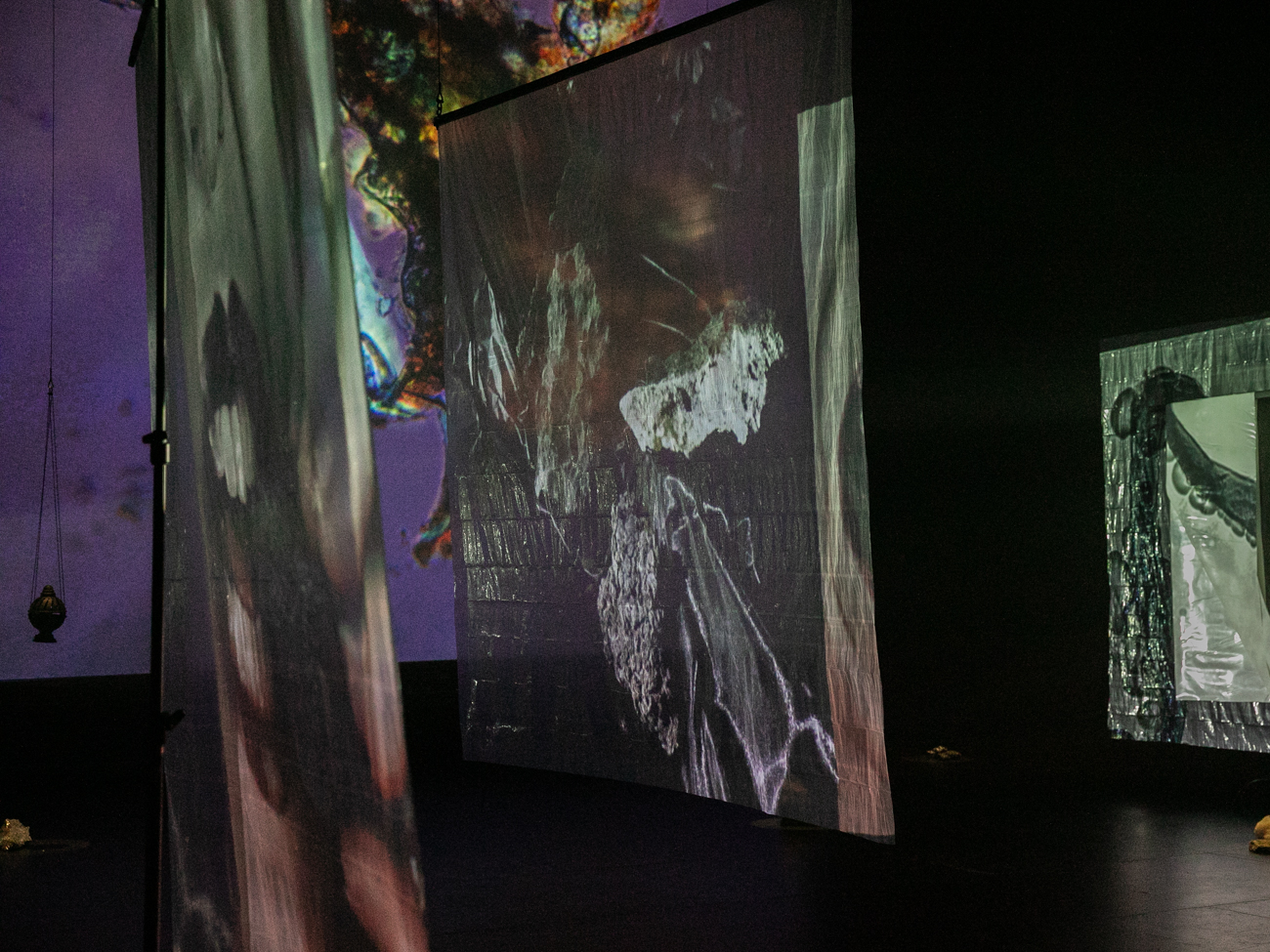

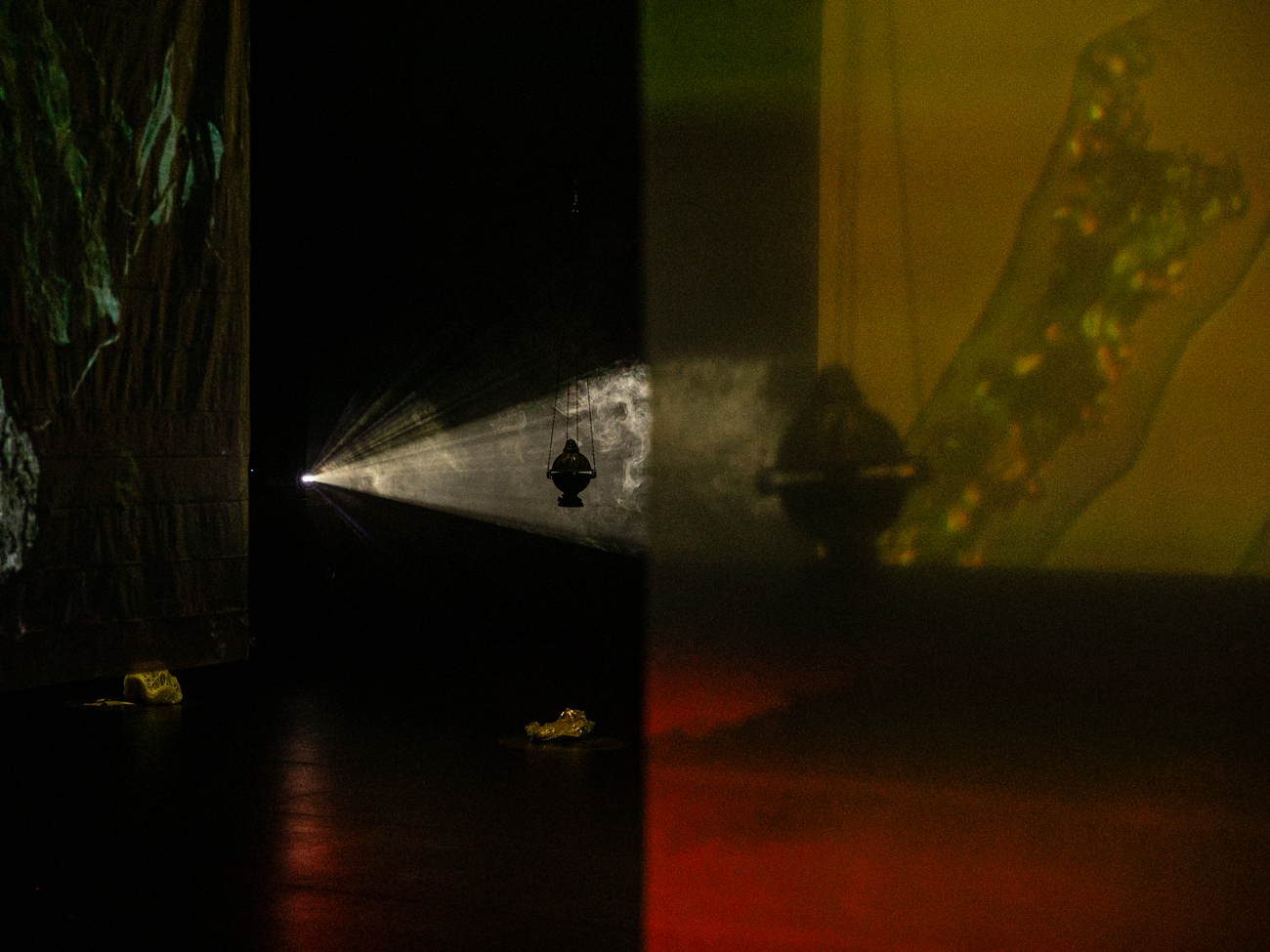

Multi-modal installation at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, Troy, NY

scent, fog, video, ambisonic sound, 3D printed incense burners, poly-plastic sheeting, found anthropogenic rocks

A series of custom screens made from plastic poly-sheeting and four hanging incense thuribles turned EMPAC’s Studio 1 into a space for meditative reflection of (and from inside) various scalar and material agencies of the Anthropocene. Live and captured microscope projections showed the artists’ search for microplastics in local tap water, while other videos showed the consumption of edible clay rocks (geophagy) and edible plastics. Hanging censurs filled the atmosphere with petro-aesthetic scents designed to replicate the affect of wet asphalt and plastics.

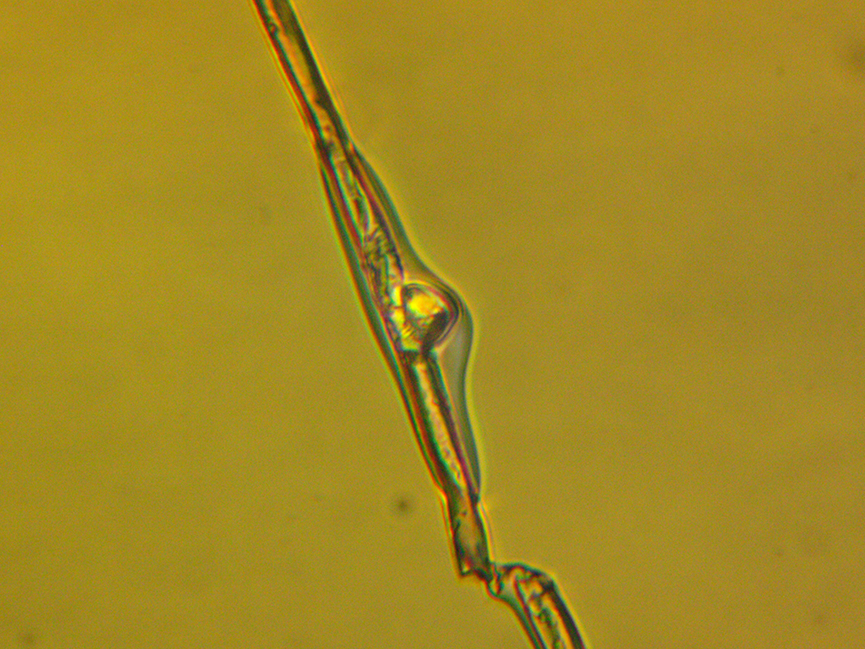

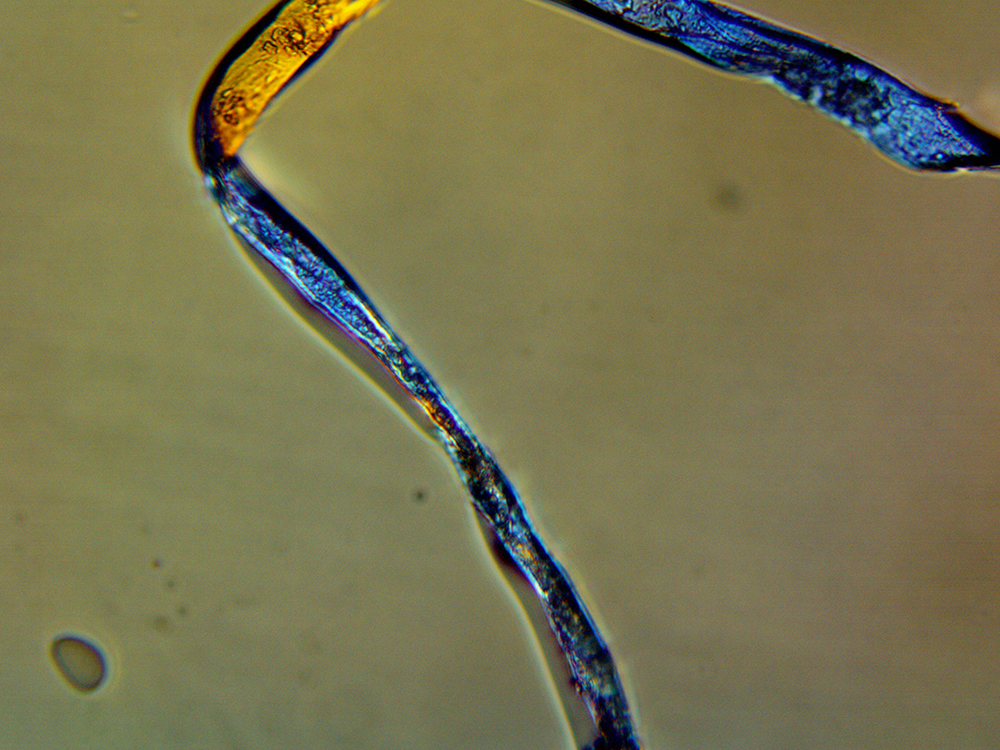

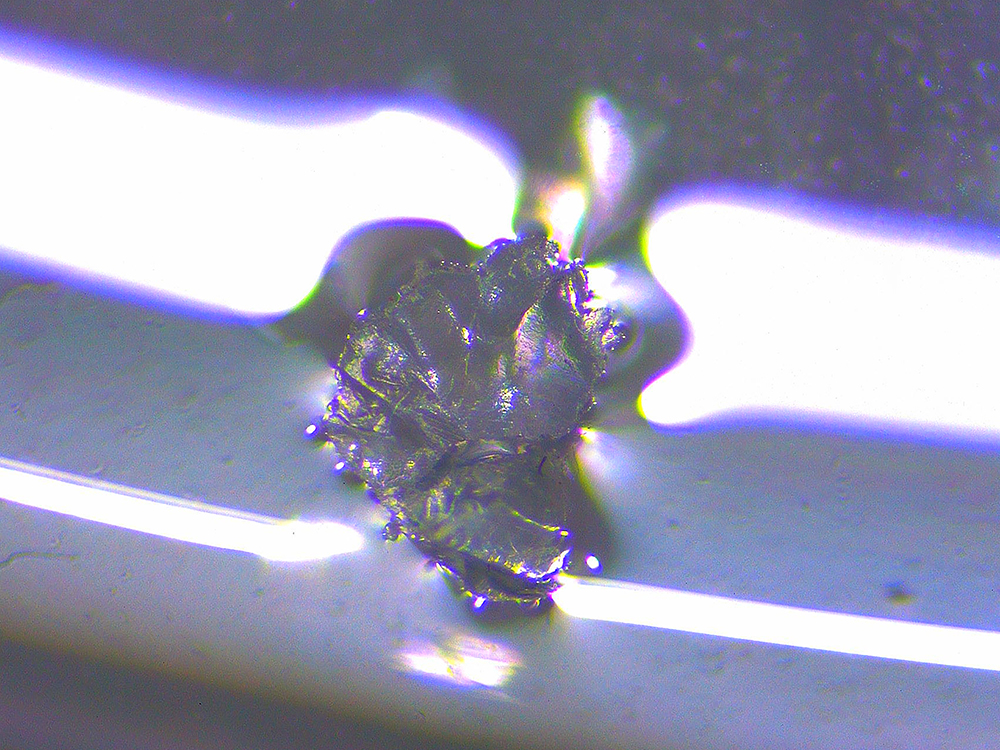

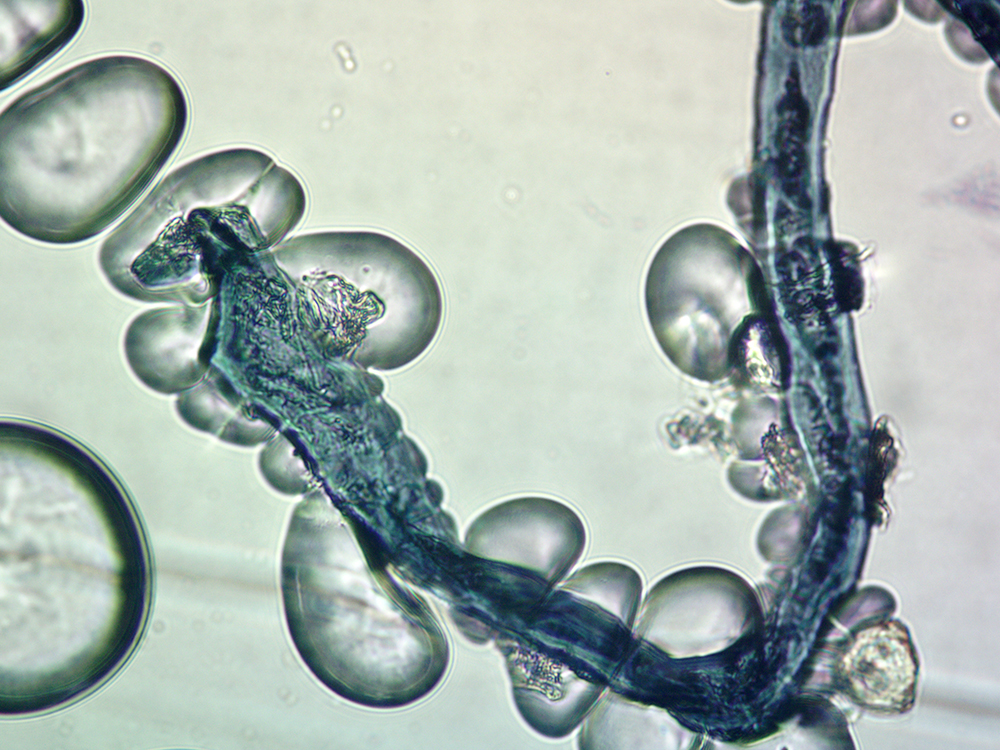

Microscopy images of microplastics cupatured in collaboration with Sarah Cadieux at RPI, a project supported by NATURELab, Kathy High, and Ellie Irons.

Microscopy images of microplastics cupatured in collaboration with Sarah Cadieux at RPI, a project supported by NATURELab, Kathy High, and Ellie Irons.

This multi-modal work provides a space for sensing where boundaries and distinctions breakdown—where the limits of one body become fuzzy with another, when detritus finally becomes landscape again, when the distinction between natural and human-made is no longer functional. Are the microplastics in my blood considered waste? Or are they ... human? Microplastics have been found in placenta and infant feces, meaning that babies are born with plastic in their bodies, a new kind of original sin. The question now might be “How to Not be Well.” In a wellness-plagued culture that too-often seeks purity, how do we learn to live as exposed and toxic bodies. Writer Sophie Strand declares: “I Will Not be Purified.” Michelle Murphy asks us to take seriously the acceptance of what she calls alterlife—life already, irrevocably altered by ongoing ecological violence. But life altered is also a capacity for becoming something else. It is life no longer waiting for the apocalypse to arrive. It is building worlds from within the disaster.

The exhibit also features an olfactory entrance chamber designed for sensory deprivation of the senses which most often take primacy in scientific knowledge production (sight, sound, and even touch). Before entering the main installation space, the audience stopped in this darkness to smell a single hanging sachet containg the scent of a complex perfume designed to remind visitors of asphalt and plastics. The smell alluded to toxicity without actually being toxic, reninding the audience of the agency of invisible nonhuman materials. Microphones captured their reactions to the perfume, which were incorporated into the main installation soundscape on a 3 minute delay.

The subjectivity and corporeality of olfaction does not preclude it from being a valid form of knowledge of our environment, and in fact, may be a benefit to understanding the lived realities of ecological collapse. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, smell was a legitimate way to understand environmental changes, as toxic industrial pollution was frequently reported via its noxious odor. Smell provides evidence of manufactured risks that may be unperceived by the naked eye, pervasive in late industrialisms.

The subjectivity and corporeality of olfaction does not preclude it from being a valid form of knowledge of our environment, and in fact, may be a benefit to understanding the lived realities of ecological collapse. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, smell was a legitimate way to understand environmental changes, as toxic industrial pollution was frequently reported via its noxious odor. Smell provides evidence of manufactured risks that may be unperceived by the naked eye, pervasive in late industrialisms.

Anthropogenic Geology materials archive—

A ‘materials archive’ distributed across the floor as terrain contained objects typically left out of natural history museums, which I suggest are falsely separated from “natural” geology. The collection of hybrid rocks are ones formed in the aftermath of industrial processes, including from incinerators, glass-making factories, military operations, plastic extruders, urban paving, steel mills, and garbage incinerators. Some are shrink-wrapped in plastic—a gesture at geologic pressure through time, pressing these objects into a record of after nature.

A ‘materials archive’ distributed across the floor as terrain contained objects typically left out of natural history museums, which I suggest are falsely separated from “natural” geology. The collection of hybrid rocks are ones formed in the aftermath of industrial processes, including from incinerators, glass-making factories, military operations, plastic extruders, urban paving, steel mills, and garbage incinerators. Some are shrink-wrapped in plastic—a gesture at geologic pressure through time, pressing these objects into a record of after nature.